Race is a Choice

May 12, 2021

By Kenny Xu and Christian Watson

Kenny Xu is the President of Color Us United, founded to fight government, education, and media racialization of America.

Christian Watson is a contributor for Color Us United.

Kamala Harris had a choice, being the daughter of Jamaican and Indian immigrants. On the campaign trail in the 2020 election cycle, she often presented herself as Black – emphasizing her studies at the Historically Black Howard University and saying to Joe Biden in the Democratic Primary debates: “my neighbor, her parents told her she couldn’t play with us because we were Black.” When she was selected as Biden’s Vice President, she ran a media campaign that emphasized her Asian-American roots. But when directly questioned about her personal identity during an interview, she said “I am who I am.” She described herself simply as “an American,” according to the Washington Post.

Mrs. Harris clearly sought to not fit into just one box. If the Vice President of the United States needn’t conform to imposed racial categories, why must we as Americans continue to succumb to be divided on racial boxes like “Black” and “White” and “Hispanic” or its equally horrendous counterpart, “Asian American”? (What in common does a newly arrived Filipino American have with a Japanese American whose grandparents came here in the 20th century?)

We anticipate several criticisms from our friends of the Left on this matter. The first is that Mrs. Harris has the power to “transcend” race, whereas ordinary Americans don’t. This is a lie. First, you transcend race, you gain the muster to see yourself as an actualized individual; then, your problems become like the problems of any other man – rejection, social failure, hunger, and thirst – and you can see those problems as endemic to the human condition rather than your specific racial condition.

What man has not undergone rejection? What man has not been told ‘life is not fair?’ Racism is just one of the many ways people experience social failure, which is just another academic term for ‘life.’ By no means, however, do we have to internalize this racism or seek a grand narrative around it that pertains to the colors of our skins. What does race mean to us? Our argument is simple and fair: race means to us what it means to us.

The historical decisions of numerous African Americans confirm the primacy of choice over blind acceptance of one’s circumstances, even circumstances that were primarily caused by racial division and segregation. In Tulsa, Oklahoma during the early 20th century during the height of Jim Crow, a colony of freedmen established the Greenwood District. Greenwood, originally an uninteresting sight, transformed into the crown envy of Oklahoma – and even the country. The black residents of Greenwood invested in land and produced around 200 businesses, including hotels and a proto-taxi services. Their success was so enormous that six of the town’s families owned many of the planes in Tulsa’s airports. They completely changed the perceptions around them that Black people were lazy and unable to build institutions of their own. Yet, if these former slaves had succumbed to the dominant narratives of the day surrounding Black people, Black Wall Street would never have been possible. It was burned to the ground by white mobbers in 1921, because it stood as a symbol of Black advancement and vitality.

Self-actualization, entrepreneurship, and local education among Black Americans in the turn of the 20th century, led by the intrepid Booker T. Washington, greatly increased the literacy rate of Blacks from 20 percent to 77 percent in the span of just 50 years. Even in the Jim Crow infected 1920s, former slaves realized they had a choice: to shed race or to embrace it. It behooves free Americans in the 2020s to do the same.

The great American poet Ralph Waldo Emerson, in his seminal work Self-Reliance, urges his reader to forsake old customs and pay heed to the “sanctity” of their own mind. He compellingly says the “objection to conforming to usages that have become dead to you is that it scatters your force.” The imposed narratives of so-called race, which are really made to control the individual, are “usages” that “scatter your force.” To this Emerson rebukes the narrative: “Enough. I will affirm who I truly am, independent of classification.”

Some will argue that how a person will be “perceived” in society based on their race is not up to them. And this is definitely true – but controlling other people’s finicky perceptions of us is nigh-impossible. We can only control ourselves and our attitudes to life.

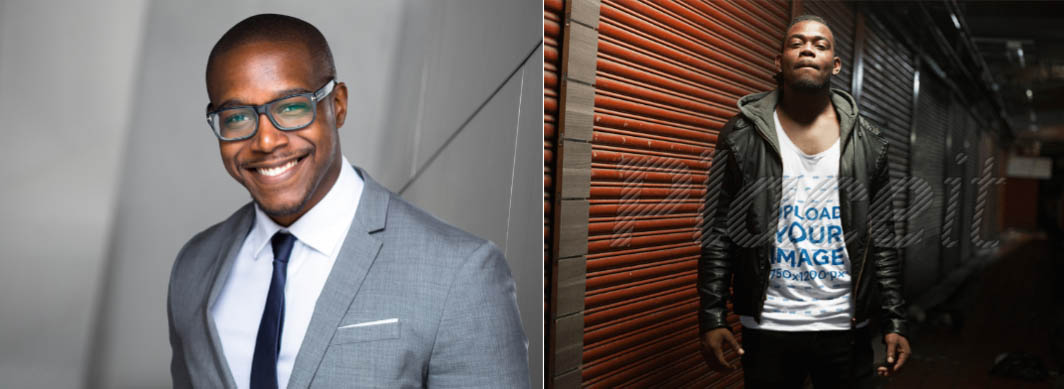

And, a professional attitude to life does pay off in the perception department. Cuddy, Glick, and Fiske’s famous BIAS map graphing stereotypes of certain populations along the dual axes of Warmth and Competence finds that although “poor Blacks” fared poorly in perceptions of both Warmth and Competence, “Black professionals” fared extremely well in both, even higher than “Whites” in Warmth. Black Americans, like all Americans, have great adjustability in the way they present themselves and associate with society that has more to do with things they can control rather than cannot.

The difference in perception of these two men extends far beyond race.

A great many Americans of darker color skin, in our history and in present day, have made the choice to see and foretell an America without race, in keeping with the great American tradition of expanding the circle to include more people under its umbrella. Frederick Douglass, in an interview with the Washington Post over his marriage to a white woman, Helen Pitts, believed in this ultimate destiny of America: that “there is no division of races. God Almighty made but one race. I adopt the theory that in time the varieties of races will be blended into one… You may say that Frederick Douglass considers himself a member of the one race which exists.”

You may call Douglass naïve. (He was not naïve.) But we select a different term for the master orator: visionary.

The problem is too many Americans of minority descent have structured their attitudes in the opposite way: around a false narrative that solidifies their race as a category of immutable victimhood, both externally and internally, and these choices have implications for how they view themselves in relation or contention with the world. 74 percent of Black Americans view their own race as “extremely” or “very” important, forcing them to contend with their own specters and internalized perceptions as a side constraint of contending with the world.

On the other hand, only 15 percent of Whites view their racial identity as extremely or very important to them. The majority of Americans of European skin view themselves as White, yes, but they don’t take stock in it. It is bad enough to contend with the world. It is worse when, in your contention, you feel artificially limited by your race (although this mainly applies to the only 50 percent of Black Americans, 23 percent of Hispanics, and 25 percent of Asians who feel that their race significantly hurts their advancement).

Think about the difference between the lived outlooks of two Black authors. We present first the immensely race conscious, race burdened author Ta-Nehisi Coates, who writes bleakly of white supremacy: “Our triumphs can never redeem this. Perhaps our triumphs are not even the point. Perhaps struggle is all we have.” Compare this attitude, of which ‘struggle’ is glorified and success deemed inaccessible, to that of fellow Black author Zora Neale Hurston, who writes: “I found that I had no need of either class or race prejudice, those scourges of humanity. The solace of easy generalization was taken from me, but I received the richer gift of individualism.”

Choices and attitudes have consequences. Every choice we make aligns us or separates us from what we perceive as America – as either a unbending, racist nation or as a nation in which the principles may still hold true, where we can succeed. Coates made his choice. And Hurston made hers.

All this for the primary message: the world puts categories upon us, but we define what they mean.